If you rely on a private well (or manage wells for a facility), casing in is one of those “out of sight, out of mind” topics that becomes very real the moment water quality changes, pressure drops, or a routine test comes back abnormal. In simple terms, casing in refers to the well casing doing its core job: lining and protecting the wellbore so the well stays structurally stable and surface contaminants don’t enter your water supply. When casing integrity is compromised, problems can cascade fast — because the casing is the backbone of the well’s safety and performance.

What “casing in” means in a water well

In a drilled water well, the well casing is the pipe lining installed in the borehole to support the sides of the well and reduce pathways for contamination. A complete casing system also includes a casing seal (often cement or bentonite) placed around the casing to prevent surface and near-surface water from migrating down along the outside of the casing.

So when people say casing in, they’re usually pointing to one of two things. They might mean that the well casing has been installed and sealed correctly. Or they might be asking whether the well casing is still functioning as a protective barrier after years of use.

That distinction matters, because many “casing problems” are not just a cracked pipe. Sometimes the casing is intact but the seal around it has degraded, or the well cap is letting contamination in at the top. Guidance from EPA and university extension programs repeatedly emphasizes the role of secure caps and sanitary seals in preventing entry into the well.

Why casing in matters for safety and performance

A properly protected well is not only about water clarity. It is about preventing contaminants from reaching the aquifer zone your pump draws from and stopping short-circuit pathways that bypass natural filtration. State and public-health guidance describes the casing seal’s purpose as preventing surface or near-surface water from gaining access to the casing and migrating downward to the groundwater source.

When casing integrity or sealing fails, the risks can include bacterial contamination, nitrates and agricultural chemicals, and debris intrusion. Texas A&M’s extension material highlights how a cracked casing can allow fertilizers, nitrates, oil products, or pesticides to enter if spilled or present near the well.

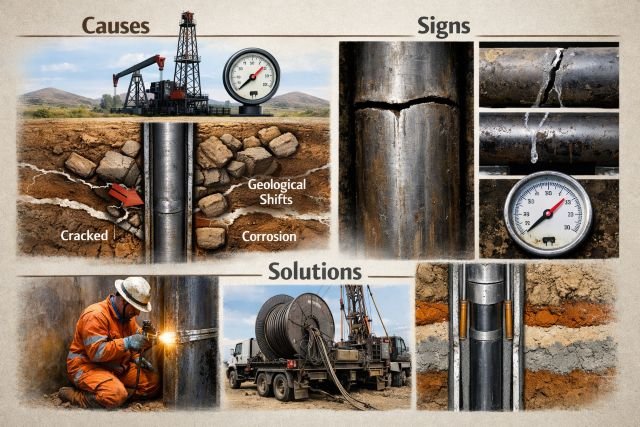

Casing in problems: the most common causes

Most casing issues develop over time, and they tend to be caused by a combination of environment, construction details, and maintenance history.

Corrosion and material degradation

Steel casing can corrode, thinning the wall and eventually creating pinholes or weak points. Industry and professional groundwater publications discuss corrosion in well components as an ongoing operational issue, especially as infrastructure ages.

PVC casing does not rust, but it can crack from physical impact, UV exposure above ground, or stresses from soil movement.

Annular seal failure or poor sealing

Even if the casing pipe itself is fine, the space between the borehole and casing is often sealed with bentonite or cement to block water migration. Water Well Journal notes that annular seals are placed to provide a barrier to migration and that poor materials or installation can leak and allow cross-contamination.

This is one of the most overlooked “casing in” failures because the casing pipe looks normal from the surface, yet contaminants can still travel along the outside of it.

Well cap and wellhead vulnerabilities

A standard cap can leave gaps that allow insects, small animals, or surface water intrusion. Penn State Extension explains that a sanitary well cap uses a rubber gasket for a tight seal and includes screening for airflow, reducing entry pathways compared with caps that leave air gaps.

EPA’s private wells guidance also recommends installing a well cap or sanitary seal to prevent entry into the well and avoiding pollutants near the well area.

Ground movement, settling, and freeze-thaw effects

Soil heave and settling can stress the upper casing and the seal zone. Over time, repeated micro-movements can open small pathways that become large problems during heavy rain or snowmelt.

Mechanical damage from workovers or site activity

Casing and the wellhead area can be damaged by vehicles, landscaping equipment, construction, or repeated servicing. In broader well engineering literature, casing damage commonly manifests as deformation, rupture, or seal failure, compromising well integrity.

Warning signs your casing in system may be failing

Some casing problems show up dramatically. Many start as “odd” changes that come and go. The key is noticing patterns.

Water changes after rainstorms

If water becomes cloudy, develops odor, or tests positive for bacteria after heavy rain, that pattern often points to surface influence. The casing seal is specifically intended to prevent surface or near-surface water from migrating down the casing pathway.

Sediment, grit, or frequent filter clogging

Sediment in aerators and appliances can mean formation material is entering the well or that well components are degrading. Even when not directly caused by casing failure, persistent sediment is a strong reason to inspect casing integrity and sealing.

Taste and odor shifts with no plumbing explanation

Organic smells, mustiness, or sudden metallic tastes may signal contamination pathways or corrosion effects. When changes are new and repeatable, it is worth treating them as a system-level issue rather than only a household plumbing issue.

Visible wellhead issues

Look for cracked or tilted casing above ground, a loose or damaged cap, pooling water around the well, or signs that insects or small animals could enter. Penn State Extension points out that non-sanitary caps can leave an air gap that allows entry risks, while sanitary caps are designed to seal tightly with the casing.

Quick diagnosis table: symptom and what it can suggest

| Symptom | What it may suggest | Why it relates to casing in |

|---|---|---|

| Cloudy or smelly water after rain | Surface infiltration pathway | Seals/cap exist to block near-surface water migration |

| Coliform-positive test after storms | Bacterial entry pathway | Caps and grout seals are installed to prevent surface contamination |

| Grit in fixtures, frequent filter clogs | Sediment intrusion | Can be tied to structural integrity or seal problems |

| Oil/chemical taste near work area | Local contamination risk | Cracked casing can allow pesticides/fuels to enter near the well |

Proven solutions for casing in issues

The best fix depends on where the failure is happening: at the wellhead, in the casing pipe, or around the casing in the seal zone. The most effective approach is usually layered: correct the pathway, then sanitize and verify with testing.

Improve wellhead protection and drainage first

If water pools near the well, re-grade the area so runoff flows away. If the cap is not sanitary, replace it with a gasketed sanitary well cap appropriate for your casing diameter and configuration. Penn State Extension describes why sanitary caps reduce common entry pathways, and EPA explicitly recommends well caps or sanitary seals to prevent entry.

This step alone resolves a surprising number of “mystery contamination after rain” cases.

Verify and restore the casing seal where needed

If the issue appears after rain even with a solid cap and good drainage, the annular seal is a prime suspect. Water Well Journal explains that the annular seal is intended as a barrier and that leaks can allow cross-contamination within the well.

Seal restoration is typically not a DIY task. It requires proper materials, placement, and often specialized equipment.

Repair casing leaks with professional methods

When casing itself is compromised, fixes may include installing an internal liner or other approved repair approaches. A key point is that casing leaks are not just “water loss.” They can introduce surface runoff, fertilizer residues, bacteria, and other contaminants into the well.

If you suspect a leak, prioritize a professional inspection and do not rely on unapproved patches, especially for potable water systems.

Address contamination safely and confirm with testing

If bacteria is detected, remediation typically involves correcting the entry pathway first, then disinfection, then retesting. Virginia Tech’s well water material notes that sanitary caps and grout seals are primarily installed to prevent surface contamination, particularly bacterial contamination.

Because contamination can recur if the pathway remains, testing is what turns a “repair” into a verified solution.

Manage sediment intrusion without masking the cause

If sediment is the main complaint, cleaning and redevelopment may help short-term, but the long-term solution is stopping the intrusion source. That can mean addressing seals, screens, or compromised zones that are no longer isolated.

When replacement becomes the smartest option

If the casing is extensively corroded, deformed, or repeatedly fails after repairs, replacement may be more cost-effective and safer. In broader casing integrity research, deformation, rupture, and seal failure are recognized as well integrity risks.

Real-world scenarios

A homeowner notices the water looks fine most of the year, but it turns cloudy after heavy rain and sometimes tests coliform-positive. The yard slopes toward the well, and the cap is a basic non-gasketed style. In many cases like this, improving drainage and switching to a sanitary well cap removes the direct entry pathway. EPA recommends well caps or sanitary seals to prevent entry, and extension guidance explains why gasketed caps reduce gaps that allow surface water and pests into the casing.

A small facility sees frequent sediment clogging in filters and reduced pump performance over a few months. A well contractor identifies casing-related integrity concerns and recommends repair plus redevelopment. While sediment can have multiple causes, a casing and seal evaluation helps ensure the well is not acting as a conduit for unwanted material migration.

Practical prevention tips that actually work

Casing in failures are cheaper to prevent than to fix. Keep runoff flowing away from the well area and avoid mixing, storing, or applying pollutants near the wellhead, as EPA recommends for private well protection.

If you live near agriculture or regularly fertilize, treat well protection as part of routine property maintenance. A cracked casing or poorly protected well area increases the chance that nitrates, pesticides, and other pollutants can reach groundwater.

Test strategically. If your water changes after storms, test after storms, not only on a calendar schedule. Pattern-based testing is one of the fastest ways to confirm whether casing in protection is failing.

FAQ

What is casing in

Casing in refers to having a properly installed and intact well casing system that supports the wellbore and helps prevent contaminants and surface water from entering the well, especially when paired with an effective casing seal and sanitary well cap.

Can a cracked casing contaminate well water

Yes. Extension guidance notes that cracked casings can allow fertilizers, nitrates, oil, pesticides, and other pollutants to enter the well, and leak pathways can also introduce bacteria and surface runoff.

What is the purpose of the casing seal around a well

The casing seal’s purpose is to prevent surface or near-surface waters from gaining access to the casing pathway and migrating down to the groundwater source.

What is the best first fix if water changes after rain

Start by improving wellhead drainage and installing a proper sanitary well cap, because preventing entry at the top is a high-impact step recommended in both EPA and extension guidance.

Conclusion

When casing in is done right and maintained over time, it protects both the structure of the well and the safety of your water. When it starts failing, the first clues are often behavioral: water changes after storms, recurring bacteria findings, sediment that won’t stop, and visible wellhead vulnerabilities. The good news is that many cases improve dramatically with wellhead upgrades, better drainage, and verified sealing integrity. EPA recommends using a well cap or sanitary seal to prevent entry and avoiding pollutants near the well, while construction guidance emphasizes the role of casing seals in blocking surface and near-surface migration.

If you suspect a casing-related issue, treat it as a safety problem first and a convenience problem second: correct the pathway, sanitize if needed, and confirm with follow-up testing. That is how you turn a casing in repair into a proven, lasting solution.

Leave a comment